The fate of the peace plan for Gaza announced at the White House on Monday 29 September is not yet decided. Because Hamas accepted the hostage return part of the proposed deal, while seeking negotiation of other parts, US President Trump ordered Israel to stop bombing. It did not immediately do that though the Prime Minister’s office said it was preparing for “immediate implementation” of the first stage of the plan.

There has, of course, been considerable coverage of the plan in the news media. Some focusses on its prospects, including the impact of divisions within Hamas about it, along with the matter of whether Trump will impose a deadline for Hamas’ acceptance and how long it might be. There has been some coverage of gaps and uncertainties in the plan and plenty of advocates have been out there to disparage or support the plan. And there’s been quite some discussion about whether President Trump prevailed over Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu in crafting the plan, or the other way round.

But, so far as I have seen, there has been little dispassionate coverage of whether it is actually a good plan, whether it will work. So this post is my clause-by-clause assessment of the Gaza peace plan.

Peace is a tricky business. An 1100 word document containing 20 points is not a treaty, is not legally binding, and is bound to contain a number of generalities and broad statements of intent. That leaves plenty of room for uncertainty to creep in. Nonetheless, it is a serious document and not the first one to address how to end the war in Gaza. It builds on the never-implemented January 2025 agreement, which itself built on the never-implemented May 2024 agreement. With those foundations, there ought to be some key issues on which there is clarity but there should also be some latitude for uncertainty, interpretation and further discussion.

In sum, not surprisingly, what comes out is mixed – some strengths, some weakness, some areas of clarity and some confusion.

NB: 4 October: The first two paragraphs above have been updated to reflect Hamas’s response, Trump’s order, and Israel’s continued bombing of Gaza. The last two paragraphs in my analysis of clause 3 below are also an update.

Overall aim

The plan begins with two straightforward points of principle.

1. Gaza will be a deradicalised terror-free zone that does not pose a threat to its neighbours.

2. Gaza will be redeveloped for the benefit of the people of Gaza, who have suffered more than enough.

Ceasefire, hostages, prisoners and human remains

Clause 3 is the ceasefire.

3. If both sides agree to this proposal, the war will immediately end. Israeli forces will withdraw to the agreed-upon line to prepare for a hostage release. During this time, all military operations, including aerial and artillery bombardment, will be suspended, and battle lines will remain frozen until conditions are met for the complete staged withdrawal.

The ceasefire is the starting point for peace and also where the potential complications begin. If you jump ahead to clause 15 about the proposed International Stabilization Force (ISF), it is referred to as “the long-term internal security solution”. That raises the question of what is the short-term solution and, specifically, how is the ceasefire monitored and how are potential breaches investigated and evaluated? And by whom?

According to clause 15 below, the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) will hand over territory to the ISF as they (the IDF) withdraw. That is consistent with clause 3 in which everything stops and “battle lines will remain frozen until conditions are met for the full staged withdrawal”. But it leaves no specific provision for an immediate, independent ceasefire-monitoring entity, which is necessary so as to sustain the progress.

This, in short, is a clause and a process that seem not to have been properly thought through.

A point of interest is that the clause says the ceasefire begins when both sides agree to this plan. President Trump, however, “ordered” Israel to stop bombing when Hamas announced it accepted part of the plan, including clause 4 on hostage return. Is that flexibility a good sign because it means stopping the violence is more important than legalistic detail (even though a peace agreement should in the end be packed out with detail and have the force of law)? Or is it a bad sign because it means things haven’t been thought through so there’s going to be a lot of policy-making on the hoof, leading to uncertainty and disagreements?

Probably the flexibility is both a good and bad sign. If that sounds paradoxical, that’s how peace processes can be. That is why peace is a tricky business.

Clause 4 covers the return of hostages. This is as fundamental as the ceasefire, because once the hostages are returned Israel has lost what little is left of its casus belli.

4. Within 72 hours of Israel publicly accepting this agreement, all hostages, alive and deceased, will be returned.

Given this tight timeline, one issue that might arise is if the halt in Israeli military activities (clause 3) is not synchronised to the second with Israel’s public acceptance of the agreement. It is the kind of detail that can undermine everything. If an entity to handle the short-term ceasefire-monitoring had been specified in clause 3, the problem would still be real but more manageable.

Hostage release leads onto the prisoner exchange in clause 5 and the return to Gaza of deceased Gazans.

5. Once all hostages are released, Israel will release 250 life-sentence prisoners, plus 1,700 Gazans who were detained after October 7th 2023, including all women and children detained in that context. For every Israeli hostage whose remains are released, Israel will release the remains of 15 deceased Gazans.

It is not clear who the “dead Gazans” are. I guess the working assumption is that they are victims of war but that is not said explicitly, nor whether they are combatants or civilians.

A more important uncertainty, since a key aim of this plan is that Hamas no longer has any role in governance of Gaza (clauses 9 and 13 below), is the matter of who is to receive the remains of dead Gazans and verify their identities. Is it the families and, if so, how are they to be found? Or is it an authority that does not yet exist? Or is it an international agency? In clause 8 below, the Red Cross / Red Crescent is expected to share responsibility with the UN for the distribution of humanitarian aid in Gaza responsibility. The implicit thought may be that it should also be involved in the process of returning human remains.

Amnesty

Clause 6 is both a big idea and a potential mare’s nest. It offers amnesty for those want to take a peaceful path and give up their weapons and it allows Hamas members to leave safely.

6. Once all hostages are returned, Hamas members who commit to peaceful co-existence and to decommission their weapons will be given amnesty. Members of Hamas who wish to leave Gaza will be provided safe passage to receiving countries.

It would be more straightforward if amnesty went to those who give up their weapons, with no other conditions attached. But the logic of demanding more is pretty clear and attractive for Israel and its citizens. It might well be politically impossible for any Israeli government to accept only decommissioning weapons as the criterion for amnesty.

But that logic introduces difficulties because who is going to judge (and how) whether individuals genuinely commit to peaceful co-existence?

Further, will members of Hamas who do not commit to peaceful co-existence and do not give up their weapons be allowed to leave safely? It is what it says here but is that what is really meant? Militant, angry, trained opponents of Israel heading off to congregate and make new plans elsewhere?

If that is not what is meant and, indeed, if there is any doubt about the meaning of this clause, there is a shedload of trouble ahead.

Aid

Clause 7 is a mess.

7. Upon acceptance of this agreement, full aid will be immediately sent into the Gaza Strip. At a minimum, aid quantities will be consistent with what was included in the January 19, 2025, agreement regarding humanitarian aid, including rehabilitation of infrastructure (water, electricity, sewage), rehabilitation of hospitals and bakeries, and entry of necessary equipment to remove rubble and open roads.

The meaning of “full aid” is so unclear that the next sentence tries to give it some content but remains vague. What does “consistent with” actually mean? – “the same as”, or “somewhere pretty close to”, or “meeting the same degree of need, making allowance for the fact that more people are in greater need than eight months ago, so therefore somewhat more than”?

The January agreement had a clause referring to humanitarian aid, without specifying the “level”, but was not about reconstruction, for which considerable development aid will be needed. Given the impossibility of delivering humanitarian aid properly to Gaza over the past 18-22 months, and in view of the controversies that have swirled around, and not least in view of the way that Israel has ignored the International Court of Justice’s injunction in March 2024 that Israel must enable humanitarian assistance to the people of Gaza, this part of the plan needs sorting out. It will be hard for it to retain credibility if there is any more lawyering and weasel words from Israel and its supporters about humanitarian assistance to Palestinians in Gaza. They need it and must get it.

Clause 8, however, concerning the delivery of aid is not a mess.

8. Entry of distribution and aid in the Gaza Strip will proceed, without interference from the two parties, through the United Nations and its agencies, and the Red Crescent, in addition to other international institutions not associated in any manner with either party. Opening the Rafah Crossing in both directions will be subject to the same mechanism implemented under the January 19, 2025 agreement.

This is another fundamental part of the plan and of prospects for peace and it is encouraging that the task is entrusted to independent bodies with the proven capacity to fulfil the task, if properly resourced to do so.

Transitional power

Clause 9 gets into the politics of the planned transition to peace. This is about power and government. If the peace plan is agreed and implementation begins, this is one of the clauses where the rubber hits the road in the first year, and then again, all the time for a very long time. The stakes are high when it comes to getting the governance arrangements right.

9. Gaza will be governed under the temporary transitional governance of a technocratic, apolitical Palestinian committee, responsible for delivering the day-to-day running of public services and municipalities for the people in Gaza. This committee will be made up of qualified Palestinians and international experts, with oversight and supervision by a new international transitional body, the “Board of Peace,” which will be headed and chaired by President Donald J. Trump, with other members and heads of state to be announced, including former prime minister Tony Blair. This body will set the framework and handle the funding for the redevelopment of Gaza until such time as the Palestinian Authority has completed its reform program, as outlined in various proposals, including President Trump’s peace plan in 2020 and the Saudi-French proposal, and can securely and effectively take back control of Gaza. This body will call on best international standards to create modern and efficient governance that serves the people of Gaza and is conducive to attracting investment.

There is no easy, quick or widely accepted recipe, toolbox or methodology for governing a fragile, contested, war-affected territory. Complexity, obstacles and outright obstructionism should be expected on just about everything. In the case of Gaza, the purpose of this plan is to remove the body that has been running it for almost 20 years, creating both an administrative void and a potential political abyss.

Against that background, the idea of “a technocratic, apolitical” committee to run Gaza has obvious attractions. It is not far from the models of Bosnia and Herzegovina and of Kosovo after their wars in the 1990s and into the 2000s. In Bosnia and Herzegovina there was the High Representative of the international community , while in Kosovo there was the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General; they oversaw peacebuilding in those countries.

But the responsibilities of the committee proposed for Gaza go wider and its mandate may last longer. There is no timetable for handing over its authority, which is not a problem in itself since arbitrary timetables are among the banes of peacebuilding. The end of the mandate will be when the Palestinian Authority (PA) has reformed itself to the satisfaction of the Board of Peace that oversees the work of the committee. Deciding what is satisfactory in PA reform is more than likely to be an issue around which disagreement will cluster, with potentially explosive consequences.

There are intrinsic limitations to the idea of “a technocratic, apolitical” committee. The problem is that, like war, peace is fundamentally a political question. So is development. The apolitical technocrat is all too often either blinded as to what is at really at stake in a policy choice, or makes a choice that is actually deeply political, in that it consciously favours one group over another, but depicts it as non-political. This is where internationals so often get into difficulties in conflict-affected states and in peacebuilding, because they don’t see the political implications of decisions they think are merely commonsense, while the locals only see the politics of it, and only see that in terms of who wins, who loses.

But the problems that may arise with this “technocratic, apolitical” committee are of a different order, for it will be overseen by a Board of Peace chaired by possibly the least apolitical person in the known universe. The record of his administration this year suggests that everything is interpreted and understood through the lens of political partisanship and advantage. It would be ill-advised to expect Trump to lose that habit all of a sudden. He has been closely aligned with Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu for years. He has, in addition, shown himself capable of changing policies and what he says about them at extraordinary speed.

On the one hand, while the committee may strive to be apolitical and technocratic, its work will be supervised by a Board led by somebody who doesn’t do apolitical. On the other hand, just a few examples of Trump’s characteristic on-again off-again approach to policy will have a deeply unsettling effect on Gaza and the “technocratic, apolitical” committee that is trying to run things.

Economic development

Clause 10 is another big idea and is about an important part of any vision of a peaceful future for Gaza (or anywhere) – prosperity. It carries an unmistakeable personal stamp.

10. A Trump economic development plan to rebuild and energise Gaza will be created by convening a panel of experts who have helped birth some of the thriving modern miracle cities in the Middle East. Many thoughtful investment proposals and exciting development ideas have been crafted by well-meaning international groups, and will be considered to synthesise the security and governance frameworks to attract and facilitate these investments that will create jobs, opportunity, and hope for future Gaza.

It is ambitious, which is not only good but probably essential. But the ambition is not grounded. It comes out as a bunch of high-flying phrases. So if somebody signs up to this, what are they actually signing up for?

A panel of experts will consider plans and see how to attract investment and create jobs. It is far from a bad idea but the clause is clear about one thing: there is no plan, for it says, NB, “A Trump economic development plan…will be created…” The commitment is not clear and who will be making the commitment is also not clear. There is more rhetoric about “thriving modern miracle cities” and “exciting development ideas” than substance.

Apart from this lack of clarity and certainty, which is perhaps unavoidable, there are three problems with the clause.

One is that Gaza does not look like an attractive investment opportunity to anybody and for anything except construction. “Miracle cities”, if the phrase means anything, are not just buildings; they are hives of activity, technology, culture and human interaction and creativity. Does an investor outside of the construction industry see that potential in Gaza now? For nearly two years, Palestinians have been struggling to stay alive in Gaza. Based on experience among other war-ravaged populations, there will be extraordinary creativity and spirt among ordinary Palestinians, finding ground level solutions to daily challenges. But taking part in building a miracle city? – well, maybe – it’s a fine hope but it will take a lot to make it more than just a hope.

The second problem is that outsiders often see investment, jobs and the offer of a prosperous future as the key to building and sustaining peace. Experience of peace building since the end of the Cold War in 1989-1991 shows it is part of the picture but not the whole story. While economic deprivation is a major cause of the grievance and resentment that feeds conflict and mobilises fighters as violence starts and escalates, the prospect of prosperity is only one among several factors for peacebuilding. Violent conflict can get deep into the soul and do untold damage. So economic development is important but don’t ignore reconciliation, rights, healing and the delivery of basic services.

And the third problem is that the emphasis on cities and, indeed, all the images of urban destruction in Gaza since 7 October 2023 possibly distract us from the destruction of agriculture. Gaza was once largely self-sufficient in basic foods. That came under increasing pressure over the 15 years before 2023, largely as an Israeli response to Hamas taking over in Gaza. By 2022, the UN categorized some two-thirds of Gazans as experiencing moderate or severe food insecurity. If Gaza is to get to a condition where it does not need outside support to meet basic needs – i.e., if the humanitarian tap can be safely turned off – ensuring that there are regular meals in every household will be fundamental. Restoring food systems needs to be at the core of this development plan.

Like clause 10, clause 11 offers a good idea with a personal stamp but with no specification.

11. A special economic zone will be established, with preferred tariff and access rates to be negotiated with participating countries.

Freedom of movement for Gazans

Clause 12 sounds good and important and is perfectly clear in its intention and substance.

12. No one will be forced to leave Gaza, and those who wish to leave will be free to do so and free to return. We will encourage people to stay and offer them the opportunity to build a better Gaza.

Whether it will work out in practice depends on the efficient delivery of massive humanitarian aid (clause 7), a fast start to reconstruction, and early headway on attracting investment into a well-structured economic development plan (clause 10).

Displacing Hamas from power

Clauses 13-15 concern the permanent exclusion of Hamas from any kind of power, role or influence in Gaza.

13. Hamas and other factions agree to not have any role in the governance of Gaza, directly, indirectly, or in any form. All military, terror, and offensive infrastructure, including tunnels and weapon production facilities, will be destroyed and not rebuilt. There will be a process of demilitarisation of Gaza under the supervision of independent monitors, which will include placing weapons permanently beyond use through an agreed process of decommissioning, and supported by an internationally funded buy-back and reintegration program all verified by the independent monitors. New Gaza will be fully committed to building a prosperous economy and to peaceful coexistence with their neighbours.

Clause 13 is the key difficulty as far as Hamas’s acceptance of the plan is concerned, though it will find much else in the plan to object to, both in what it says and in what is left out. Whether Hamas will accept or reject or try to negotiate the plan is not clear at the time of writing.If Hamas does finally accept the plan, even if modified, how unified that acceptance will be is another point of uncertainty. Rejecting peace plans has a long history among different factions in the Middle East region. It is why clause 15 below is also crucial.

14. A guarantee will be provided by regional partners to ensure that Hamas, and the factions, comply with their obligations and that New Gaza poses no threat to its neighbours or its people.

The big question about clause 14 is not primarily whether there are some “regional partners” who want to offer to guarantee the compliance of Hamas and other unnamed groups (“the factions”) with the plan, but, more significantly, whether they have the capacity and will to enforce compliance, over the long term (meaning, for decades) and yet do so in a way that does not get in the way of achieving the peacekeeping objectives set out in clause 15 and the aim of dialogue and mutual understanding between Israelis and Palestinians in clause 18 below.

International Stabilisation Force

A key part of the peace and security jigsaw is the International Stabilization Force (ISF) proposed in clause 15.

15. The United States will work with Arab and international partners to develop a temporary International Stabilization Force (ISF) to immediately deploy in Gaza. The ISF will train and provide support to vetted Palestinian police forces in Gaza, and will consult with Jordan and Egypt who have extensive experience in this field. This force will be the long-term internal security solution. The ISF will work with Israel and Egypt to help secure border areas, along with newly trained Palestinian police forces. It is critical to prevent munitions from entering Gaza and to facilitate the rapid and secure flow of goods to rebuild and revitalise Gaza. A deconfliction mechanism will be agreed upon by the parties.

“Temporary” is a reassuring word but peacekeeping forces often stay for long periods of time – 50 years in Cyprus, for example, almost as long in Lebanon, 25 years in DRC before the force’s withdrawal in 2024 with war still going on.

Apart from the disconcertingly wide range of irreducible challenges that these peace operations faced, there are obvious unanswered questions in this clause. What size will the ISF be, involving which “partners” (and are there any firm commitments yet), and commanded by whom? Similarly, how will Palestinian police be vetted, for what, and by whom?

Nonetheless, this clause has a great deal more solidity than some of the earlier ones and gives more reassurance that some systematic thinking has already gone into it.

Israel’s withdrawal of forces

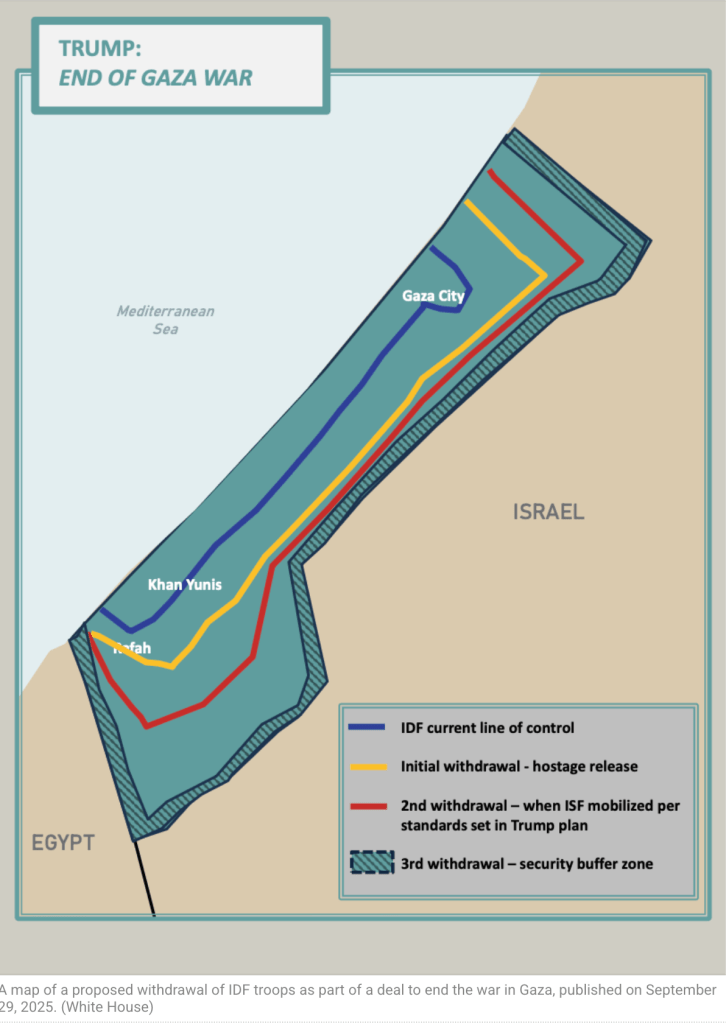

Clause 16 covers Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza. It comes with a rough map.

16. Israel will not occupy or annex Gaza. As the ISF establishes control and stability, the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) will withdraw based on standards, milestones, and timeframes linked to demilitarisation that will be agreed upon between the IDF, ISF, the guarantors, and the United States, with the objective of a secure Gaza that no longer poses a threat to Israel, Egypt, or its citizens. Practically, the IDF will progressively hand over the Gaza territory it occupies to the ISF, according to an agreement they will make with the transitional authority, until they are withdrawn completely from Gaza, save for a security perimeter presence that will remain until Gaza is properly secure from any resurgent terror threat.

At the end of the process, the plan is that there are no Israeli forces or settlers in Gaza, which was the case, with the exception of Israeli military incursions, from 2005 to 2023.

For Palestinians who remain in Gaza, much will depend on how the IDF behaves as it withdraws and, similarly, how the ISF behaves as it takes over. If it all ends up looking like military occupation by a different name, Palestinian sentiment in Gaza may be full of resentment and potential for conflict. If somehow the ISF can win Palestinians’ acceptance of it as a legitimate peacekeeper, an honest broker, nobody’s pawn, then sentiment may be more positive for building a lasting peace.

If Hamas refuses

Clause 17 says that refusal or reluctance by Hamas to go along with this plan will not be allowed to block it.

17. In the event Hamas delays or rejects this proposal, the above, including the scaled-up aid operation, will proceed in the terror-free areas handed over from the IDF to the ISF.

Since this is partly about getting aid into Gaza, it’s encouraging that the commitment to deliver aid is not contingent upon Hamas’s acceptance. But, according to the clause, if Hamas does not meet whatever deadline Trump sets, Israeli forces remain in charge and operational where they want to remain in charge and operational until they decide to decare an area “terror-free”. Clause 17 therefore looks all too much like one more slightly disguised attempt to put Hamas over a barrel, a form of pressure to which that organisation has not generally responded compliantly.

Dialogue

Clause 18 sets out the aim of a dialogue process that will be initiated.

18. An interfaith dialogue process will be established based on the values of tolerance and peaceful co-existence to try and change mindsets and narratives of Palestinians and Israelis by emphasising the benefits that can be derived from peace.

I know something about dialogue between conflicting parties over the past 30 years in a variety of settings, both at government level and between citizens active in civil society.

The goal of changing mindsets and narratives is a noble one but that’s not the aim that the participants will sign up for. And expressing it openly may backfire. Participants tend to come into dialogue primarily because they want to persuade their interlocutors how reasonable they are – and how right – not because they want to change the way they themselves think. If the facilitator can find the ones who are also curious about what their interlocutors think and will say, it starts to be possible to get the listening part of dialogue functioning. And getting everybody to listen is much more important and much harder than getting them to talk.

It’s also important to recognise that the participants are individuals – not all Palestinians think the same as each other, likewise Israelis disagree with Israelis. And when Israelis and Palestinians go back to their respective homes and talk about what they heard and said, some of their friends will find it interesting and some will set out to correct their new, wrong attitudes. The process takes time before it has any chance of getting grounded and influential in the wider society. Time and patience. If it works, it will be enormously important and it is worth investing in, but carefully and with experienced facilitators.

But I don’t understand why it is described as an “interfaith” process. Is religious difference the problem? I thought it was land, political rights, power and security.

Statehood

Clause 19 gestures carefully towards a long-term future in which there is a Palestinian state. No promises.

19. While Gaza re-development advances and when the PA reform program is faithfully carried out, the conditions may finally be in place for a credible pathway to Palestinian self-determination and statehood, which we recognise as the aspiration of the Palestinian people.

It would have been non-credible either to be more specific about when statehood might happen, or to guarantee that PA reform leads straight to statehood, or to go the other way and leave the clause out entirely. But this has to be the least satisfying and, in the long term, the most difficult part of the whole process.

Predictably enough, Netanyahu has already reassured his supporters and right-wing critics alike that he does not support Palestinian statehood ever and will, in his own words, “forcibly resist a Palestinian state“.

But beyond that, take a look at this simplified UN map of the West Bank (or the detailed, complicated one if you prefer). The lighter coloured areas are those that are either controlled by the PA or jointly by the PA and Israel. The PA has no role in the darker coloured areas. The West Bank has become a patchwork and as time passes it becomes harder and harder to see how an effective Palestinian state is possible. That is the only solution that the vast majority of the world’s governments can see, but unless statehood involves Israel ceding back territory it now controls, including areas where there are settlements, it is truly difficult to see how it will work.

This is one of those arguments on which I would like to be wrong so if anybody can reconcile the map’s patchwork and independent statehood, that would be great.

Formal dialogue

While clause 18 is about people-to-people dialogue, clause 20 is about formal dialogue.

20. The United States will establish a dialogue between Israel and the Palestinians to agree on a political horizon for peaceful and prosperous co-existence.

But the clause is interestingly and undeniably vague about participation in the formal dialogue. On one side, it’s Israel; that’s clear, the government of the state of Israel. On the other side, it’s the Palestinians – not the Palestinian Authority but a group of people. It’s not clear why but there are some possible interpretations of why the PA is not mentioned here that are a long way from being reassuring.

Great summation of the Peace Plan Dan. Can Toda republish. it as a Policy brief? Cheers Kevin

Great summary of the Peace proposal Dan. Can the Toda Peace Institute republish the blog as a Policy brief? Cheers, Kevin

Absolutely, Kevin. Please go right ahead. I updated it this morning to cover Hamas’s response, Trump’s response to that, and Netanyahu’s response to him.

Thanks Dan-cheers in these crazy times. K

Pingback: The Gaza peace plan, 2 weeks in: continuing assessment | Dan Smith's blog

Pingback: The Gaza peace plan after 7 weeks: 3rd assessment | Dan Smith's blog