The first ten days of August each year are a time to remind ourselves about the effects of nuclear weapons.

1945

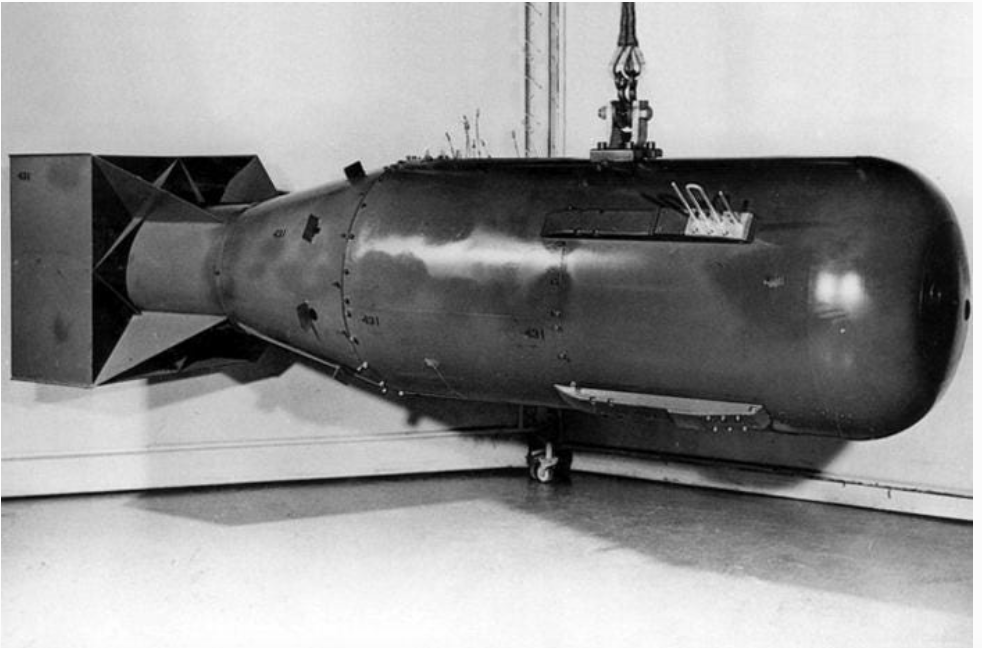

6 August 1945: Hiroshima: the first nuclear weapon to be used on a civilian target was dropped from an American aircraft and detonated about 1900 feet (580 metres) above the city. The circle of immediate and total destruction was about two miles across (3.2 km). Calculating how many people died is complicated for many reasons. The figures range from around 65,000 in early US estimates, to 140,000 by the end of 1945 according to Japanese official sources, and a range from 90,000 to 166,000 deaths by the end of 1945 according to a more recent study by the joint Japanese-US Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF).

NB: The bomb was relatively small – equivalent to about 14 kilotons of TNT in explosive power – and the nuclear reaction was very inefficient: less than 1.4 percent of the nuclear material actually fissioned.

9 August 1945: Nagasaki: war continued and a second nuclear bombing attack was authorised. The bomb was of different design and material (plutonium instead of uranium), and functioned ten times as efficiently. It detonated about 1650 feet (500 metres) above the city. Bad weather and poor visibility meant the bomb was missed its target by just under 2 miles (nearly 3 km). Early US reports put the death toll at about 39,000; in the 1970s, Japanese estimates came to a total of about 70,000. The US-Japanese RERF estimate is from 60,000 to 80,000 deaths by the end of 1945.

NB: The 21 kiloton bomb detonated over the valley in Nagasaki and a lot of the city was protected from the blast by the surrounding steep hills.

The combined population of the two cities was between 590,000 and 620,000.

Using the figures from the RERF studies, there were 150,000 to 246,000 deaths in a 5-month period, caused by two bombs – one inefficient, one inaccurate.

The effects persist over the decades with lives lost to various forms of cancer resulting from radioactive fallout. Estimating this long-term death toll is even harder than figuring out the immediate human cost. One rough estimate suggests that if there were about 400,000 survivors – the hibakusha – then there may have been about 3,000 cancer deaths among them.

These are the facts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki 1945 as far as they are known and it is easy to dig them up.

Say it again, just for the sake of it: two bombs, one inefficient, one inaccurate. This is less than the very least firepower that would be used in even the most limited of limited nuclear wars.

The years and decades since then

As the Nobel Peace Prize Committee said when announcing their 2024 award to the hibakusha movement, Nihon Hidankyo, it is “an encouraging fact” that the second time a nuclear weapon was used in war is the last time so far. There have been occasions when the world came close, among them

- President Eisenhower’s 1953 threat to use nuclear weapons against China if its leaders would not agree to negotiate an end to the war Korea;

- The 1962 Cuba missile crisis;

- The 1983 false alert of a US missile attack on the USSR.

Close and, indeed, close enough – but not too close. So far there has been a way to get back from the cliff edge. There has always been risk and danger but, mostly, political leaders have recognised the need for responsible behaviour when it comes to issues of megadeath and the survival of humanity.

Today

This month we complete eight decades of the age of nuclear weapons. This month, President Trump announced he had ordered two nuclear submarines to be deployed to the “appropriate regions” because, he told reporters, “A threat was made by a former president of Russia and we’re going to protect our people.”

The vagueness of that statement remains unclarified a couple of days later. For example, which are the appropriate regions? Had they previously been deployed in the wrong regions? The term “nuclear submarine” is also vague; did he mean submarines carrying ballistic nuclear missiles (SSBNs) or nuclear powered subs with non-nuclear weapons (SSNs – or SSGNs if they carry cruise missiles)? If he meant SSBNs or SSGNs, why would redeployment be significant, given the range of their weapons and their strategic roles?

And then there’s the “threat”. It was made by Russia’s ex-president, ex-prime minister and current deputy chair of the Russian Security Council, Dmitry Anatolyevich Medvedev. In a social media post, he took Trump to task for issuing an ultimatum – sanctions if there is no ceasefire with Ukraine – and said, “Each new ultimatum is a threat and a step towards war. Not between Russia and Ukraine, but with his own country.” Trump called that “foolish and inflammatory” and warned, “Words are very important, and can often lead to unintended consequences.” And said he had redeployed the two submarines.

It’s not nice, what Medvedev said, but it’s a bit difficult to see it as a threat requiring nuclear deployments in response, especially not if you compare it with what he says when he does want to make a threat. Like when he said that Ukraine defending its territory was a “direct reason” for Russia to use nuclear weapons. Or remarked in March 2022 that NATO countries sending weapons to Ukraine increased the likelihood of war with Russia, which could go nuclear. Or said in March 2023, after the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for his boss Russian President Vladimir Putin, “It is quite possible to imagine a hypersonic missile being fired from the North Sea from a Russian ship at The Hague courthouse.” Or indeed, earlier that year, when he called for the use of death squads against politically active Russian expatriates.

This is, by the way, the same man who, in 2008 when president of his country, enumerated five principles of foreign policy, the first of which was that international law is supreme, while the third one was that Russia would not seek confrontation with other nations.

He has also said that in Ukraine, Russia is fighting a sacred battle again Satan.

It doesn’t take much hunting online to find a whole lot of other things he has said, not excluding a prediction of a coming war between France and Germany. He seems to be a guy who says stuff. Which could also be said of Donald Trump, of course. But what Medvedev said about ultimatums is far from the most extreme thing he has said in the last few years as he has grown into the role of Putin’s hawkish cheerleader. So it is a little odd that Trump should choose this one to respond to. Of course, the reason could be as simple as the fact that, this time, Medvedev picked on Trump himself.

It could also be because the vagueness of Trump’s response means it is as rhetorical and devoid of real substance as the remark to which it responded.

There is a strong case for thinking that this spat is no more than that, doesn’t matter, and is no cause for concern or worry. That is actually the Kremlin’s official response – because “American submarines are already on combat duty” – though they were inevitably unable to resist the temptation to upbraid Trump: “Of course, we believe that everyone should be very, very careful with nuclear rhetoric.”

Overall, as the ninth decade of the nuclear weapons era begins, I do not think the world has suddenly moved any closer to the risk of nuclear war.

But I don’t like it when people in positions of power and influence try to stand tall with rhetoric about the bomb. It’s simply the wrong attitude.

Thanks for the reminder and for your perspective, Dan. We need both. Hope all is well with you. – Chic