On 6 and 9 August this year, we will mark the 80th anniversaries of the two occasions on which nuclear weapons have ever been used in war – the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.* Humanity has perpetrated and experienced a great deal of harm in the past eight decades but nuclear weapons have not been used again. Despite today’s widespread and intensifying perception of nuclear risk, the nuclear taboo survives.

That does not mean the nuclear problem has been solved, of course. It is “an encouraging fact”, as the Nobel Peace Prize Committee put it when giving the 2024 award to the movement of Japanese nuclear survivors (the hibakusha), Nihon Hidankyo. But not more than that. And honouring the hibakusha in this way was also intended as a wake-up call to those many people who until recently regarded nucleapons as yesterday’s problem.

The state of the world

The nuclear challenge is not just nuclear. To think about the nuclear challenge today and tomorrow, we need to think both about nuclear weapons themselves and about the larger context – the state of the world in the 2020s. For that reason, this post covers a fairly wide range of issues (and for that reason, reader beware, it’s a bit long).

It takes little insight, no originality and not much research beyond a brief look at the headlines to recognise that global security faces more risk and danger today than at any time since the end of the Cold War in 1989-91. Compared to the last three decades, as many of my previous posts have described (so I will spare you the details this time), the 2020s are seeing more numerous armed conflicts, with higher war fatalities and increased displacement of people, while great power confrontation has returned to levels of intensity not witnessed in over three decades, including the voicing of nuclear threats.

That much is clear. But are today’s dangers are worse than during the Cold War, in the early 1960s, for example, when there was an armoured East-West face-off in Berlin, followed by the building of the Berlin Wall, and then the 1962 Cuba missile crisis amid an accelerating nuclear arms race? Or worse than in the early 1980s as the gains of US-Soviet détente evaporated, the USSR invaded Afghanistan, and NATO planned the deployment of a new generation of missiles to match the Soviet SS-20s?

Getting the balances right

Keeping a sense of historical perspective on our current situation seems to me to be one of three kinds of balance it is is worth maintaining when exploring these issues. The history of nuclear risk reminds us that we have been somewhere like this before and got out of it. A second balance is one I have already referred to, based on the realisation that nuclear risk involves more than nuclear weapons alone. In a sense, it involves putting nuclear weapons in their place and making sure they don’t take up the whole space.

The third balance is not far removed from that. It’s about avoiding the trap of focussing only on risk. Let’s be clear, there is no point in ducking the fact that nuclear weapons do embody an existential risk. Even if only a small percentage of the number available is used, the result will be devastation on a scale not previously experienced in human history and, in essence, unimaginable. In the past year and a half I have found myself being asked to talk about the effects of nuclear weapons in a way that I hadn’t for some 40 years, since the days of the peace movement in the early 1980s; for a compact example, you could check out this from SVT’s Din guide till jordens undergång (Your guide to the world’s downfall) (starting at 14.24, finishing around 16.50) (and, don’t worry, I describe doomsday in English).

There is an undeniable if grim fascination in visualising the apocalypse. And the point is that it is important to not get over-focussed on that, to avoid being the human rabbit in the nuclear headlights. Nuclear war is a low probability, horribly high impact event: thinking about the nuclear challenge, we should fully respect the impact, and not complacently rely on the low probability, but nor should we forget those eight decades in which nuclear weapons have not been used. In a way, as long as we don’t rely on it, the low probability is a sign of hope that we can again rise to the nuclear challenge.

Nuclear arms control

All that said, let’s talk nuclear.

The world’s nuclear stockpile has been shrinking for almost 40 years, from a total number of bombs and warheads in the mid-1980s variously estimated between 63,600 and over 70,000 to just over 12,100 at the beginning of 2024. Year by year, that reduction is continuing, and will continue for some more years as old warheads that have already been retired from service are dismantled. Within the totals, however, the number of deployed nuclear weapons has started to increase. Thus far, the increases are confined to China, North Korea and, numerically much smaller, India; combined, the estimated increase from 2023 to 2024 by these three states amounted to 118 warheads – less than 1 per cent of the global total, and fewer than the number that were retired and dismantled. As statistically insignificant as that 1 per cent may look at first glance, it is a warning sign that the era of nuclear weapons reductions is probably coming to an end.

Bilateral nuclear arms control between the USA and, first the USSR, then Russia, entered crisis mode some years ago and is now almost over. The one remaining bilateral US-Russian nuclear arms control agreement is New START, agreed in 2010. Having been extended by Presidents Biden and Putin within days of the former’s inauguration in 2021, it is set to expire in early 2026. There is no sign of negotiations to renew it or replace it and no sign on either side of wanting to do so. Putin suspended Russia’s participation in the treaty in February 2023, while Trump has long regarded New START as “one-sided” and “just another bad deal that the country made”.

In the first Trump administration it was a firm policy that China should join in and bilateral arms control should become trilateral. There is something to be said for that, especially now China is well into a significant increase in its nuclear arsenal, but it will likely make any negotiations more difficult: the geometry of a balanced agreement between two sides is complex enough, but between three, it becomes fiendish. Consider the likely refusal of the USA to let its nuclear arsenal be seriously outweighed by the combined total of two countries it regards as adversaries. Alongside (or opposite) that, think about the equally likely refusals of China and Russia either to be treated as a single or combined entity for the purposes of agreement, or to be themselves as individual powers seriously outweighed by the USA’s nuclear capacity.

The geometry would only work out if there were a will to compromise for the sake of agreement.* Currently, that looks unlikely to emerge. Even if a trilateral geometry could be worked out, it begs the question – what about the others? – Britain and France, India and Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea. Like the three great powers, they too are renewing their arsenals.

The reluctance of the states that own nuclear weapons to commit themselves to further nuclear arms reductions has long been generating impatience and frustration among many of the strongest advocates for nuclear non-proliferation. Successive five-yearly meetings to review the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty seem only to produce disagreement over disarmament. The big question is, when will that process reach breaking point? Since the end of the Cold War in 1989-1991, three new states have gone nuclear – India, Pakistan, North Korea; are more waiting, in the Middle East or Northeast Asia, for example?

A new nuclear arms race?

As some key nuclear numbers begin to tick up, as the states with nuclear weapons seek to enhance their nuclear capacities, and as tensions among the three great powers and their allies sharpen, the signs are that a new nuclear arms race is gearing up. Compared to the last one, the risks are likely to be worse. The key points of competition will not just be numbers but technologies in cyber space, outer space and ocean space. So the arms race may be more qualitative rather than quantitative and the idea of who is ahead in the race will be even more elusive and intangible than it was last time round.

This will create a new techno-strategic context in which arms control will be much harder to achieve, and perhaps even to discuss, not only because it will (or should) be multi-party, but because the old largely numerical formulae of arms control will no longer apply. Among the multiple dimensions of these changes, quantum technologies will likely have a major impact on cryptography, and thus on the security of systems, as well as on global observation and monitoring. Until now, the working assumption has been that, since nuclear-powered submarines have the whole ocean to hide in, they are effectively invulnerable. Thus, submarine-launched ballistic missiles would always be available for use in the last resort, and were therefore a fail-safe deterrent that would ensure the last resort would never be arrived at. But detecting submarines in the ocean depth is easier today. That is a new source of instability.

Use ’em or lose ’em is not a principle any sane person should want to see applied to nuclear weapons.

Advances in missile defence are a further source of instability. A pipe dream in 1983 when Ronald Reagan launched the Strategic Defense Initiative, widely derided as Star Wars, it is now seen as a realistic prospect, a field in which the USA is generally regarded as in the lead but with China and Russia also developing significant capabilities. The USA’s rationale for investing in missile defence has shifted over the years. As proposed by Reagan in 1983, the rationale was summed up in his rhetorical question, “What if free people could live secure in the knowledge that their security did not rest upon the threat of instant U.S. retaliation to deter a Soviet attack, that we could intercept and destroy strategic ballistic missiles before they reached our own soil or that of our allies?” The dream, however, far outstripped the technology. As the prospect became more realistic in the past decade, the emphasis was on traditional nuclear deterrence against the big states and missile defence against states regarded as ‘rogue’, such as North Korea. More recently, with the Biden administration’s 2022 National Defense Strategy, deterrence by the threat of retaliation, based on nuclear strike weapons, is augmented through deterrence by denial, based on missile defence.

As attractive as all this looks to the one who might possess the defence, if one side is invulnerable to nuclear attack (the Reagan dream), then, in strategic theory, nuclear deterrence won’t work against it. Missile defence is the anti-nuclear shield that allows its holder to use the nuclear sword. Inevitably, the prospect of missile defence is encouraging investment in technologies to circumvent it.

One component of the coming arms race will be the attempt to gain and maintain a competitive edge in artificial intelligence, both for offensive and defensive purposes (e.g., as part of the means of, on one side, strengthening missile defence and, on the other, of circumventing it). AI has a wide range of potential strategic uses and its careless adoption could significantly increase nuclear risk. The key to understanding this is the capacity to handle huge amounts of data quickly. Quantum technologies may also be part of this story. These technologies could contribute to arms control by strengthening the capacity to monitor compliance with any agreements that are reached. But as the new technologies speed up decision-making in crisis, there is also the risk of a war as a result of miscommunication, misunderstanding or even pure technical accident.

To my mind, the reason why nuclear war is a low probability event is because starting one would be insane – an obvious act of self-destruction. There are no circumstances in which it makes sense, even if missile defence makes further advances, even if nuclear submarines can be found more easily than they can today, even if you think you have a comprehensive technological advantage. The reason why there is any probability at all is that it might be an unintentional war, in which, perhaps, the ill-luck of a hi-tech glitsch is compounded by human fallibility against a background of hostility and mutual suspicion.

That risk was real enough in September 1983 when information about five missiles launched from the USA and targeted at the USSSR appeared on a Soviet officer’s computer screen. It was a time of heightened tension, only a few weeks after a Soviet fighter shot down a Korean airliner that had strayed into restricted Soviet airspace. Humanity was saved from nuclear catastrophe because Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov did not fully trust the early warning software and thought a nuclear strike with just five missiles was illogical. Had he believed the information, he would have passed it up the line and, though there is no certainty either way, his superiors, thinking they were under attack, might have launched the attack themselves.

Will future Petrovs also have time to decide? Will they have the opportunity, will there be Petrovs in the loop?

Back to the state of the world

The biggest part of the nuclear challenge today is the toxic geopolitical environment, with hostility between the great powers, Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, confrontation over Taiwan, tensions on the Korean peninsula, the global divisiveness and polarisation sewn by Israel’s destruction of Gaza, and uncertainties about where US policy will go when Trump 2.0 begins.

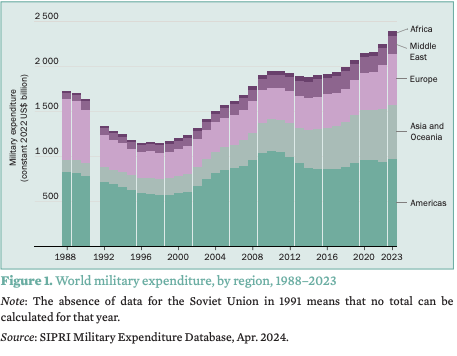

Global military spending is at its highest ever level – US$2.443 trillion in 2024 – having risen for nine straight years, the longest run of increases that SIPRI’s Military Expenditure Database records. This persistent increase in global military spending reflects a widespread perception of insecurity.

The USA is responsible for 37 per cent of the world total. The spending of the other NATO states adds up to 18 percent; they are almost all boosting their military spending further, and are and will be under pressure from Trump to do more, quicker. China, the world’s second largest military spender, responsible for 12 per cent of the world total, has increased its military spending for 29 consecutive years, the longest unbroken streak recorded by any country.

As high as these figures are, a careful look offers even more cause for concern. The global economic burden of military spending is not exceptionally large by historical standards. In 2023, military spending took up 2.3 percent of global GDP. Looking back to two moments in the Cold War, a World Bank estimate utilising SIPRI data indicates the comparable figures were 5.9 percent in 1963 and 4.2 percent in 1983. This suggests that, though adjusting state budgets may be politically contentious with negative social effects as other needs go unmet, there is in principle plenty of potential for world military spending to rise yet higher.

It would be unwise to assume that military spending will soon be at peak.

Conflict and world disorder

As well as raising the risk that a war that nobody wants could start as a result of misunderstanding and miscommunication, hostility between the great powers is having a destructive effect on international order – on the United Nations and on its capacity to manage other world problems.

As I discussed in a series of posts on world order in 2024, the high number of armed conflicts today is a key marker of a deteriorating security horizon. In 2010, there were 31 armed conflicts, but 59 in 2023. Among them are

- Russia’s war in Ukraine since 2014, drastically escalated in February 2022;

- The escalation of the conflict between Israel and Palestine that started on 7 October 2023 when Hamas made its incursion from Gaza into Israel to which Israel has responded with massive devastation of Gaza;

- The civil war in Sudan, which has forcibly displaced 9.2 million people;

- Renewed violence in eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which drove 250,000 people from their homes in early 2024, adding to the 6.9 million people already displaced by persistent violent conflict over two decades;

- Warfare in Myanmar, which has pushed almost a million Rohingya into neighbouring Bangladesh displaced over two million displaced people inside Myanmar.

Nowhere did it seem that international actors—whether third-party governments, the United Nations system or regional organizations—were able to help manage the conflicts or move them towards termination.

Ecological insecurity

These risks exist against a backdrop of ecological crisis. This is another problem that the institutions of the international order seem unable to handle properly. It is existential.

Surveying climate change brings no greater relief than surveying the rest of the international scene. 2023 was the hottest year since 1850, and probably for 125,000 years, and 2024 was almost certainly even hotter. On 22 July 2024 the Earth experienced its warmest day since records began; that month, on some days, the temperature in the Antarctic winter was around 28°C warmer than normal.

The Paris Agreement of 2015 set the goal of limiting global warming to “well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” (i.e., the average temperature of 1850-1900), while trying to stay below a 1.5°C increase (Article 2.1). Almost a decade on, November 2024 was the 16th month in a 17-month period for which the global-average surface air temperature exceeded 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Not only is the average temperature in the process of surpassing 1.5°C, we are on track to go well above the 2°C level. In fact, the current trajectory is towards approximately 3°C above the pre-industrial average before the end of this century.

That’s disaster territory. Among the consequences, long before 2100, will be an increase in the frequency of deadly humid heatwaves, and the passing of important global tipping points such as the big ice sheets collapsing in Greenland and the West Antarctic, permafrost thawing, and the death of coral reefs.

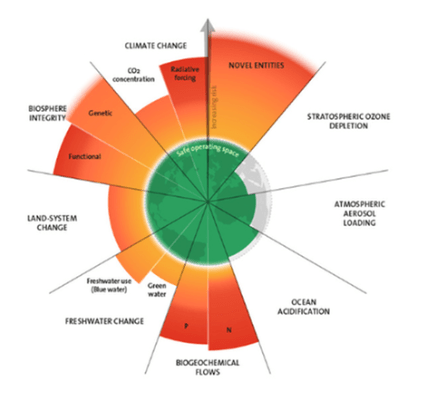

And as serious as climate change is, the ecological crisis goes beyond the climate issue alone. When looking at levels of pollution of the air, soil, sea and freshwater along with loss of biodiversity and biomass: all trends are in the wrong direction. Research led by the Stockholm Resilience Centre over the years has identified nine planetary boundaries – points that must not be passed in ecological damage, or humanity moves outside the “safe operating space” we have known for millennia into an environment that is unknown and less supportive of human welfare. At the last check-up on planetary health, six of the boundaries had been breached and one was getting close.

The natural foundations on which all social and economic life is based are changing and weakening, with profoundly concerning implications for peace and security. As the effects of ecological crisis unfold, this will have further geopolitical consequences as governments decide how to handle the unprecedented challenges and problems their societies face, and where they will position themselves on the spectrum between all-out international cooperation and throwing up the barriers against all-comers.

Facing the challenge

As explored more fully in my series of posts on world order in 2024, the global institutions are currently unable to manage conflict, handle the ecological crisis or achieve disarmament. Neither the UN and its various agencies, nor regional organisations like the African Union, nor the international financial institutions like the World Bank, nor the great powers and their alliances are handling these major, epoch-defining challenges well. Thinking about how to face up to any one of them therefore necessitates thinking about the institutional deficiency that lies behind and links them all.

As I said at the outset, if we are discussing the nuclear challenge, that is actually just a part of the discussion. The other part is world order. What could be done about each of them?

On world order

On world order, the first thing we need to see is a better, more supportive context for dialogue, compromise and agreement. The three great powers are not able to generate that context. There is too much shouting going on, not enough listening, and that will probably get worse during Donald Trump’s second term as US President.

In these circumstances the small and medium powers, civil society, academia and the private sector have to stand up and insist on cooperation to solve shared problems. It will not be easy or straightforward but the only way to achieve security today is through international cooperation.

Part of the problem is that disorder at the top has freed up objectors and stand-outs to hold up agreement by consensus and reduce the substance of agreements to the lowest (i.e., the weakest and most ineffective) common denominator.

There are issues on which the consensus principle could safely be dropped. Climate change numbers among them because if the biggest emitters curb their emissions, global warming will start to slow down. Were that to happen, the influence of the rich fossil fuel producers would diminish and the 2° Paris target would start to become realistic.

In short, when it is impossible to get everybody cooperating, then those that can work together should work together, never mind the rest.

This may serve to emphasise the point that cooperation is not idealistic. It is a pragmatic, viable approach to fundamental issues of social, economic and political organisation. Despite the free-rider problem, when some get away with benefitting from a public good to which they do not contribute, placing a premium on cooperation contributes directly and significantly to the success and well-being of any organisation, community, group or society.

Facing the multiple challenges of today, cooperation is the new realism. And the good news, as shown by too many studies to cite neatly, but here is one example addressing a different issue, tax evasion – the good news is that cooperation works.

On nuclear weapons

As part of building a better context for dialogue and a stronger ethic of cooperation, there needs to be more information to feed more widespread awareness and understanding of the existential threat nuclear weapons pose. My generation grew up as the nuclear threat grew. For the past 30 years it has been realistic to pay nuclear weapons less heed but now that has to change. A new generation will come to understand that mature and balanced behaviour by political leaders is essential in a nuclear-armed world and, further, that more nuclear weapons do not buy more security.

At the same time as public consciousness deepens, there needs to be more and better training for diplomats in matters of nuclear arms control – the technologies of verification, the experience of verifiably removing nuclear weapons and nuclear capacity. There will be a new generation in diplomacy as well as among the public. And this technical and diplomatic expertise needs to spread among the non-nuclear-armed majority of states.

This can make possible initial small steps towards reducing risk: hotlines, transparency, even informal understandings and formal agreements – no first use of nuclear weapons, nuclear-free zones. These will form guardrails against disaster and be the prelude to renewed reductions of nuclear weapons that will have to be agreed by the great powers because the pressure on them to do so will be irresistible.

By way of conclusion

Following that line of thought, I remembered President Dwight Eisenhower. During his eight years in office from January 1953, the first steps were taken towards a massive expansion of the US nuclear arsenal, with the USSR doing likewise. And in 1953 he threatened to use nuclear weapons against China if its leaders would not agree to negotiate an end to the war Korea.

But he said some good things as well. Among them, in his farewell presidential address, he gave us the concept of the military-industrial complex. And in a 1959 discussion with UK Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, broadcast on radio and TV, he said,

“I like to believe that people, in the long run, are going to do more to promote peace than our governments. Indeed, I think that people want peace so much that one of these days governments had better get out of the way and let them have it.”

________________________

- This post is an edited version of a lecture I gave in the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum on 2 December at the invitation of the PCU Nagasaki Council for Nuclear Weapons Abolition and the Research Centre for Nuclear Weapons Abolition at the University of Nagasaki.

Note

* The obvious precedent is the Five Power Treaty on naval disarmament in 1922 that set limits on the total tonnage of capital ships in the navies of France, Italy, Japan, the UK and the USA. The limits were, approximately, 500,000 tons for each of the UK and USA, understood as global powers, 300,000 for Japan and in the vicinity of 200,000 tons each for France and Italy. So a precedent exists but as an historical parallel it has limited value since the five powers were post-war allies ands victors.

Pingback: Kärnvapenhotet ökar – men motståndet lever