Amid the cacophony of overblown claims both for and against, what is so bad about Trump? Or, put the other way round, what is so good about him? Or, to ask my question properly, why is he such a polarizing figure, so it seems that one group supports him and what he stands for in their eyes just exactly as much as another group loathes him?

I think part of the answer, at least, may be what I am choosing to call the non-singular systemic.

There are obviously a lot of issues on which Trump is loathed by one lot and loved by the other in the USA. But I am looking at the question from an international perspective so I will leave US politics out of it. On the other hand, I think you might see at the end, if you look into it, that the challenge of the non-singular systemic applies to important domestic issues as well as international ones.

In an outside-the-USA perspective, scanning through both traditional and social media, there is obviously a wide range of contentious issues on which people love or loathe the past and future President – his likely approach to the war in Ukraine being a big one.

But beyond specific issues, and without under-estimating their importance, I’m looking at four categories of concern about what Trump’s second presidential term might mean for issues people care about.

Alliance

The first is the question of alliances. Seen in global terms, this is the narrowest of the four categories – strong in Europe and among countries such as Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, and of some concern in some other countries but not so profoundly. The problem for US allies is that Trump seems to take a completely transactional, what’s-in-it-for-us approach to every question. He doesn’t get the idea that, in an alliance, there’s such a thing as the common good to which all members contribute according to their capacities.

It’s worth recalling that it was because Trump couldn’t grasp the idea of shared interest in an alliance and US benefit gained from it, that his Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, called him a fucking moron.

The UN and world order

If Trump doesn’t get the idea of shared interest among a group of like-minded states in an alliance, it’s no surprise that he double doesn’t get it in the United Nations. World order, which, as regular readers of this blog know, bothers the hell out of me, is of limited and sometimes seemingly zero concern to Trump. Again, the approach is transactional, which means he sees no intrinsic worth in international commitments and obligations, let alone unstated but generally accepted norms, on the world stage. He sees the benefit in agreements that he thinks are to the USA’s advantage; he will not see it in others. If you can’t give a quick and practical answer to the what’s-in-it-for-us question, you’ve lost him.

The incoming administration’s likely actions on commitments like the Paris Climate Agreement of 2015 and on global institutions such as the World Trade Organization and the World Health Organization are part of this second category of concern about Trump 2.0.

Trade

The third, perhaps surprisingly, is trade. You’d think a businessman (as he and his supporters never stop telling us he is and super good at it too) would understand trade but he seems not to. He may understand trading and might even be good at it. I have no idea. But about the issue of trade, the surprisingly narrow limits of his understanding are revealed by the way he focuses on whether the USA runs a trade deficit with an individual trading partner – mostly China and Mexico, often the EU. The idea that you could have a surplus with some, a deficit with others, a balance with another lot, and do well out of the trade system as a whole doesn’t seem to have crossed his mental horizon. For him, trade is zero sum whereas, historically and globally, trade on fair terms is win-win.

Nature

And fourthly, there’s the natural environment. Trump’s policies on the environment, his expressed scepticism about climate change (inconsistent as that has been over the years), and his Cabinet choices for energy and as head of the Environmental Protection Agency raise a lot of hostility and concern. But Trump has often spoken of his love for the environment, for clean air and crystal clean water.

If we take him at face value, the problem is not that he doesn’t like nature. Rather, the problem is that he doesn’t get the interconnections between all its different elements – between, for example, climate change and air pollution, between climate change and the hydrological cycle, between all of them and loss of biodiversity.

Alliance, the global order, trade and the environment – what do these have in common?

My first answer was to think about world order and the natural order.

But now I think it goes beyond the question of order and the disruption that Trump brings.

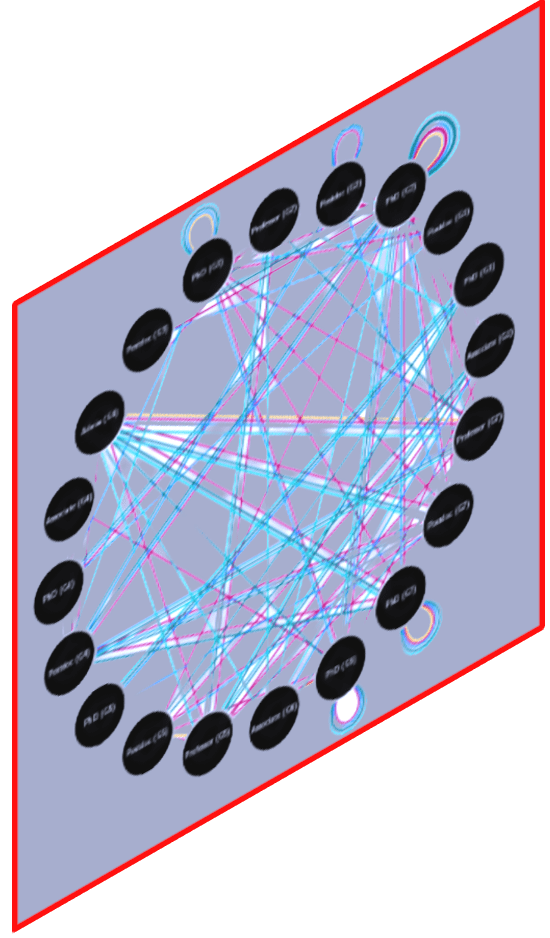

What is in common among these four sets of issues is that each involves multiplicity – of actors, of levels, of interactions, of consequences and connections to other issues.

And it is that multiplicity – or the non-singularity of it all – that Trump doesn’t get or like.

But it goes a bit further than that. The problem for Trump, I think, is not just the numbers involved. More than that, it is that there are linkages and connections between all the actors and factors, levels and issues. The way that trade is not just about buying and selling stuff but about the shape of society; the way that ecological disruption is linked to migration, health and geopolitics, which means alliance is linked to it as well; and world order, or lack of it, is part of everything from human rights to the air we breathe to the risks of war or pandemic.

Trump doesn’t seem to refer to or acknowledge the idea of system as a way of understanding these relationships and, therefore, responding to the problems and challenges. So the issue in question here is not just the non-singular nature of things, it’s also the systemic aspect of it.

All the issues I’ve mentioned and more besides are spheres of internal interconnections and every sphere is connected to the others. Like it or don’t like it, that’s just the way the world is.

And that, I think, is at least part of the reason why Trump is both loved and loathed. He is loved by those who find his implicit rejection of non-singularity and system refreshing. He is loathed by those who think his lack of concern for system and non-singularity means he may ruin something that is extremely important, somewhat intricate, constructed by interlinkage, and therefore perhaps delicate.