It is all very well to argue, as I did in my two most recent posts, that far-reaching international cooperation is essential to solve critical world issues and, furthermore, that there are issues on which it is evidently possible. But that does not solve the problem – the world order is in shaky condition and there is no consensus on how to fix it. Now’s the time to have a stab at what to do when consensus is lacking.

This lengthy post is the last in a series on world order. The series is based on the introductory chapter to the SIPRI Yearbook 2024. Successive posts have looked at the origins and history of the world order, the causes and dynamics of violent conflicts, issues of norms and law, the role of the UN, and, looming over it all, the superordinate challenge of our time – the ecological crisis. At the limit, the question is whether the world order is fit for purpose.

We can agree on the need for change but …

There is plenty to object to in the current world order, whether because it is unfair, anachronistic or simply not effective enough.

- Unfair: the great powers and the richest countries have privileged positions;

- Archaic: born in the 1940s (with European roots 300 years earlier), before many of today’s states got independence;

- Ineffective: arms control is fading; conflicts proliferate with risks of escalation in their region (like Israel’s war on Gaza) or even globally (like Russia’s war on Ukraine and tensions over Taiwan); the ecological crisis continues to deepen and the world keeps getting warmer; hunger continues to rise and the risk of another pandemic persists; great powers (and some medium powers) get away with breaching the laws and the norms of international order.

But doing away with an order that is unjust, outdated and not working as well as we would like does not necessarily mean a new one will be better. And while much is wrong with the world order, there is also much that is right, such as human rights and International Humanitarian Law and the possibilities it affords for joint action on health, the environment, education and development. Even if its standards and laws get circumvented, bent or broken, and the opportunities are missed as often as they are taken up, it remains better to have them than not. A world without the constraints of law and ethics is ruled by thugs instead of merely threatened by them.

The world order both reflects raw power and constrains it. Each of its two faces is real. If there is one unchallenged great power, perhaps you don’t notice the duality so much. Clashes among great powers make it a bit more obvious, precisely because they simultaneously make word order more important and less effective.

In short, the great powers are a big part of the problem under discussion.

Yet without their engagement in working out a solution, it is hard to see one emerging.

Triggers for change?

In fact, the world order is changing. Of the three great powers, China is on the rise, Russia is declining though masking that with aggression and bombast, and the USA is kind of steady-state but lacking the elite consensus it once had about its role in global affairs. During the 2017-2020 Trump administration, the paradox emerged of all three great powers openly disliking the world order they sat on top of.

Briefly digressing on the USA, the Biden administration restored something closer to traditional US global policy. Nonetheless, the shift towards a narrower interpretation of US interests – Hamiltonian pragmatism, as it has been depicted –goes deep and may be lasting. This will be especially unsettling for European and Asian allies of the USA who rely on it both to lead on almost everything and look after their interests. The likely difference between the impact of a Trump and a Harris administration on the world order is on the pace of change, rather than whether change continues, its direction, and how severe and frequent the bumps in the road will be.

The process of change in the world order is visible at different levels: in global headlines about conflict, escalation risks and the role of outside powers; in diplomacy, whether quiet or noisy, that reveals whose influence counts most; and in behind-the-scenes horse-trading about how international institutions are staffed and run. It is seen and felt as much in what doesn’t happen – such as war crimes prosecutions and implementation of crucial agreements on the environment – as in the big events that grab everybody’s attention.

Rather than change unfolding piecemeal, might it seem better to seize the moment for a thorough, planned reconstitution of the world order?

This is probably the right time in the discussion to remind ourselves that the world order was set in place in the wake of the massive destruction and disruption of the Second World War. Indeed, each major step in the evolution from a European order originating as a war ended in 1648 to a world order set up as a war ended in 1945 – each major step over 300 years has been instigated in response to war and upheaval.

Without major war, is a seamless transition to a new world order feasible? Do we count on those who are causing the problems to solve them? And if not, then what?

A world without law and accepted norms is one that is ruled by thugs instead of merely threatened by them.

The Summit of the Future

Plan A is the UN Summit of the Future, which takes place on 22 and 23 September, the week after this essay is posted.

The summit will agree on a Pact for the Future. You could say that this series of eight posts on world order provides the foundations for a two-sided argument about the Summit and the Pact – how much they are needed versus how unlikely it is that the governments who sign up to it all will then make it work.

I would so like to be wrong. The vision is inspirational, aiming to meet the need for multiple dimensions of change. But…

But the point I want to make here is not forecasting that reality will not match the standards set in the vision. Rather, it’s about the clarity of the grand vision getting lost in the muddiness of the details of reform.

Preparation for the Summit has been packed with reports and position papers on future generations, responding to emergency, youth engagement, economic philosophy, a digital compact, international finance, outer space, information integrity, securing peace, transforming education, and UN reform. Eleven policy briefs. It’s impressive and yet it’s incomplete.

- Inequality is not systematically addressed and some of its dimensions are almost wholly ignored.

- Health: Again, not systematic despite the near-universal experience of the pandemic.

- Cities and urbanisation: I am open to correction because there is an awful lot to trek through, but I could see nothing about urbanisation and cities, even though that’s where 70 per cent of us will soon be living.

- Ecological disruption – climate change, pollution, the loss of biodiversity and biomass, decline in soil quality, increase of anti-microbial resistance, the passing of local and regional tipping points and the emergence of intrusive species: a few mentions but no discussion, yet a world order that is fit for purpose in the 21st century must sustain the natural environment and support the innovation that is required to decarbonise economies worldwide and carry through this enormous socio-economic transformation in both a just and peaceful way.

UN agencies already address some of these issues and others are not for the UN to handle in any case, so my point in mentioning the missing topics is not critical of the Summit, its originators or the UN as a whole. I’m simply saying that those preparatory materials are one way to feel the scale of the task of drawing up a blueprint for change in the world order. And the scale feels all the greater because those who must agree to make the necessary change are the main actors in the tale of the current order’s worsening deficiencies.

If the vision is inspirational but the world’s messy complexity means the details are overwhelming, what then? Perhaps, a large-scale blueprint for UN reform is simply not the way to go.

Plan B

The alternative to the maximalism of summits and blueprints is simply to press for as much cooperation as possible, between as many actors as possible – governments, companies, city authorities, civil society organisations, international institutions – whenever possible, with a focus on specific issues rather than grand schemes.

Achieving something even though the big picture remains deficient is better than sidelining the details and delaying doing anything while focusing fruitlessly on the big picture. In this approach, change is taken on in bite-sized pieces.

Even this pragmatic, practical, limited approach requires something far-reaching because the emphasis on cooperation recognises that the power of even the most powerful is limited. Acting alone in support of a narrow self-interest is no longer practicable. With nuances and variations, the main task of the leaders of great and middle powers has always been to advance national self-interest, meaning to increase their power. It is, of course, the function of a system of world order to constrain that, so that power games are played out within limits. As the current world order weakens, there is a resurgent emphasis pursuing national interest, narrowly defined. It’s time to change that, wherever, whenever, with whomever and about whatever it is possible to do so.

There are at least five sets of issues on which, regardless of their divisions, states have shared interests that can only be met by cooperation. If the number of states that can get together for common solutions to any or all of these is less than the full membership of the UN, so be it. Those who can cooperate should do so while keeping the doors open for the standouts to join in.

Three of these five issues are, as I argued in the previous post in this series, trade, cyberspace integrity and health. They both define and are defined by contemporary hyper-connectedness. Any state that seeks prosperity for the country, whatever it is they want to do with that prosperity, cannot stand to one side and dismiss the importance of trade, the pervasiveness of cyber space, or the risk that disease in one place becomes disease in many.

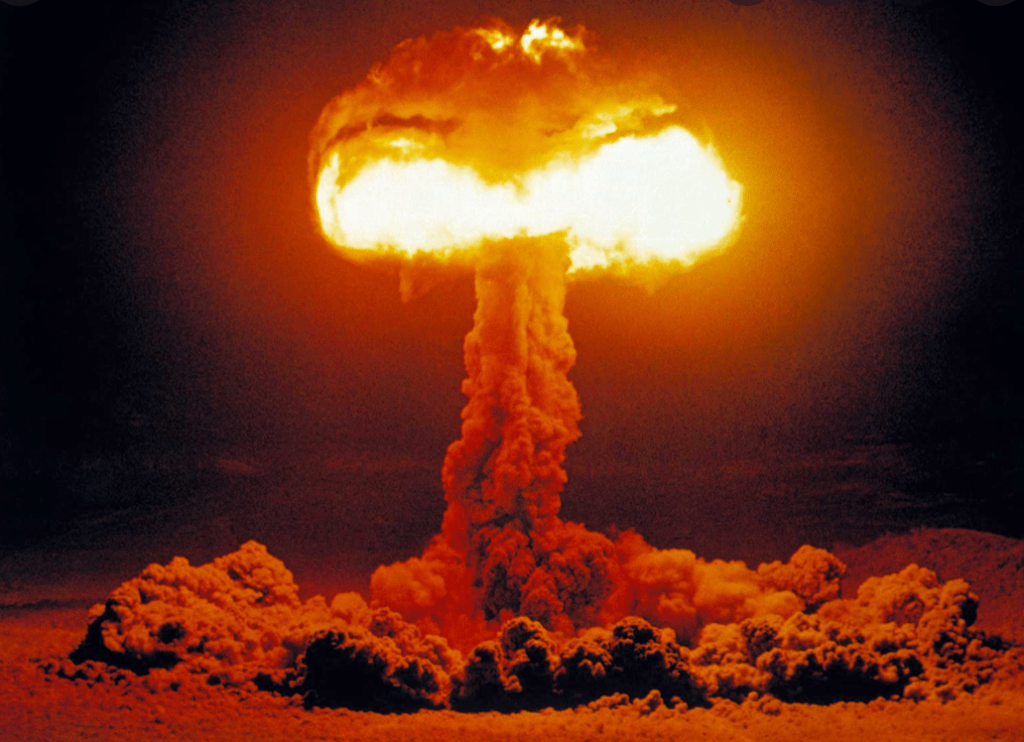

The fourth issue could for dramatic purposes be called survival, or avoidance of nuclear catastrophe.

A bit more calmly and prosaically, it could be thought of as shaping guardrails against disaster. How can we be sure that runaway escalation will not occur in local and regional conflicts and crises? How can we get leaders to dial down the rhetoric, the incautious interventionism, the rattling of different sabres, nuclear and economic? This is not a proposal for the great powers alone to define the guardrails for the rest of us, not when the record of their behaviour in the last two decades is what it is, not when they are a significant part of the problem that needs to be addressed. The great powers need to be involved and run their own backchannel contacts to agree some red lines and limits but the rest have to step up as well.

And the fifth issue, it should come as no surprise to read, is the ecological crisis. If the natural environment ceases to support humankind, interest based on power becomes a second order concern at best. Preserving the biosphere is both a core national interest and a core international interest.

The keystone assumption of this is that, while rivalries and contestations will remain, security will not be achieved by pursuing them. There could be other gains but security won’t be one of them because, ultimately, security is indivisible. It is not a zero-sum game. Rather, the key element of security today is cooperation.

The perils of ignoring that truth are revealed by considering the consequences if cooperation is not pursued. The outlines of dystopia and nightmare are sharp: international trade diminishes, and prosperity along with it; anarchy prevails in cyber space with disruptions throughout the lives of citizens and the functioning of states; in the next pandemic, vaccine nationalism is rampant; conflicts and crises escalate uncontrollably; the world warms catastrophically and, at the limit, nature no longer offers humanity a firm foundation on which to build societies.

The future may be multiplex

Not all leaders recognise the importance of cooperation across the board (or, if they recognise it, cannot muster the political resources to follow that logic). However, almost all recognise some issues on which cooperation is key. So bite-sized change and issue-specific cooperation could work.

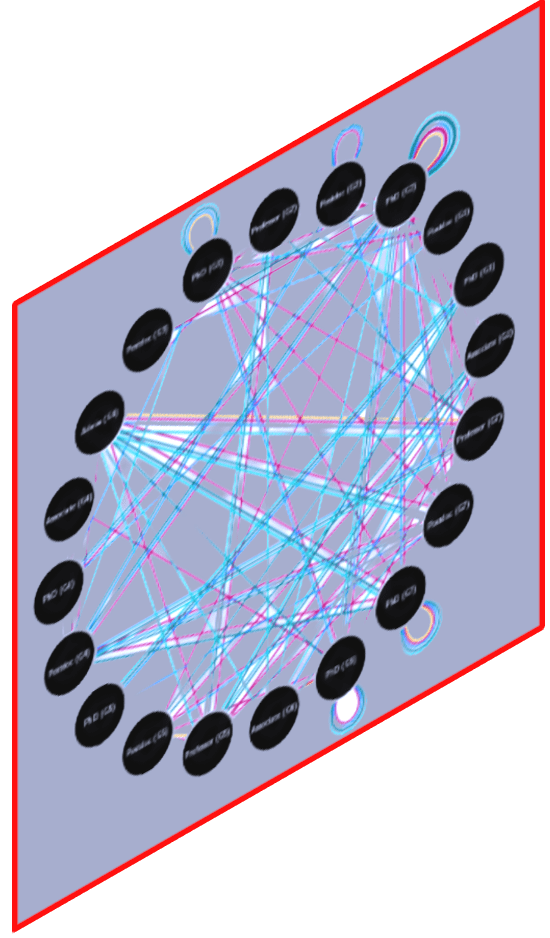

Politics being what it is, there might well be more than one cooperative coalition of states on each of those five issues and perhaps on others. It could be that, per issue, the make-up of the coalitions changes. There is in principle nothing wrong with that. While the downside is that different coalitions work with different goals and standards, the gain lies in getting away from the situation of most states agreeing half-heartedly to something they have neither means nor will to carry out.

This could be what a multiplex world order looks like – diverse, composed of distinct, interleaved parts, with different states having different degrees of influence over different issues. It would be harder to see just one or two overall leaders. It is, in other words, a way of allowing a different distribution of power to emerge along with changed constraints on the powerful, including new guardrails. Pondering the task of adapting the world order to meet the realities of today, moving knowingly in the direction of multiplexity looks like it might be more fruitful than aiming at a new blueprint.

Dear Dan,

I share your reaction to the summit draft. Much is interesting and constructive, but trying to skim it I drowned in the details.

Hans

Nevertheless, it is right to try to lift oneself by the boot straps right after heaving one-self out of swamps. You mention 1648. One could also mention 1715, 1919,1945. The collective relief after war or crisis yields moments of fresh hope and ambition — new starts. I think particularly of Cuba 1962 — the partial test-ban and NPT and absorbing the thought of MAD.

I agree that when fighting ends in Ukraine there could -should — be a period of readiness for co-operation. I agree that bit-like and issue-specific change is the more plausible. You mention trade, cyber, pandemic, nuclear and environment. Yes, I have pointed to three areas on which already a good deal of common interest and outlook between the three major players might ease cooperation : environment, pandemic and combat of international crime (notably drug.related).

However, while it is right to think of plausible areas of cooperation when shooting ends, the outlook will affected by the conditions created by the end of shooting. I am not optimistic. It seems to me that while pride and reminiscence of the past may have had some influence on Russia’s behaviour, the hard core motivation has been the anger about the prospect of getting NATO forces and weapons directly on Russia’s borders to Ukraine (and Georgia). The invasion of Ukraine, meant to be a Crimea 2 and ensure a Russia docile neighbour, was miscalculated and brought not only NATO Art. 5 but – far worse in Russian eyes –US and NATO troops and hardware to Finland and Sweden (DCA).

A dominant view in US, UK, the Nordic govts and in the Ukraine leadership now (but probably not Germany) seems to be confirmation of future Ukrainian NATO membership. Moscow may have deserved it… Yes, but continuing deterrence as the principal Western line may make for sour and bitter relations and render even bit-like cooperation hard to attain.

I think a Ukrainian commitment to no foreign troops and hardware but guarantee of military help in case of attack by Russia would be a way to the resumption of détente and cooperation that is needed. I also think Russia would be likely to pay for such a commitment by giving up conquered land (how much, I don’t know; certainly not the Crimea).

Kind regards

Hans

Every time I read your blog, I feel like I’m gaining a little more clarity on the things I’ve been pondering. You have a true gift for writing!