Most of NATO is involved, together with other states that are politically defined as part of the ‘West’, in the war in Ukraine by providing training and equipment for Ukraine’s armed forces and by supporting its government financially and politically. NATO is also involved in another way as part of the Russian narrative that presents the invasions of Ukraine in 2014 and 2022 as forced upon Russia by NATO’s incorporation of eastern European states since the end of the Cold War.

Russian spokespersons and others have treated NATO’s increasing membership as an exculpatory reason for, or a partial justification for, or a proximate cause of, or a contributing factor to Russia’s war against Ukraine. These are arguments worth looking into.

This blog post is part of a series on the world order, the pressures it faces and the condition it is in. The series is based on the introductory chapter to the recently published SIPRI Yearbook 2024, updating the evidence in places and slightly expanding the argument here and there. Focussed on the question of NATO and its changing membership since the end of the Cold War, this post is something of a digression from the main theme of the series, about a topic that keeps coming up .

Enlargement / expansion

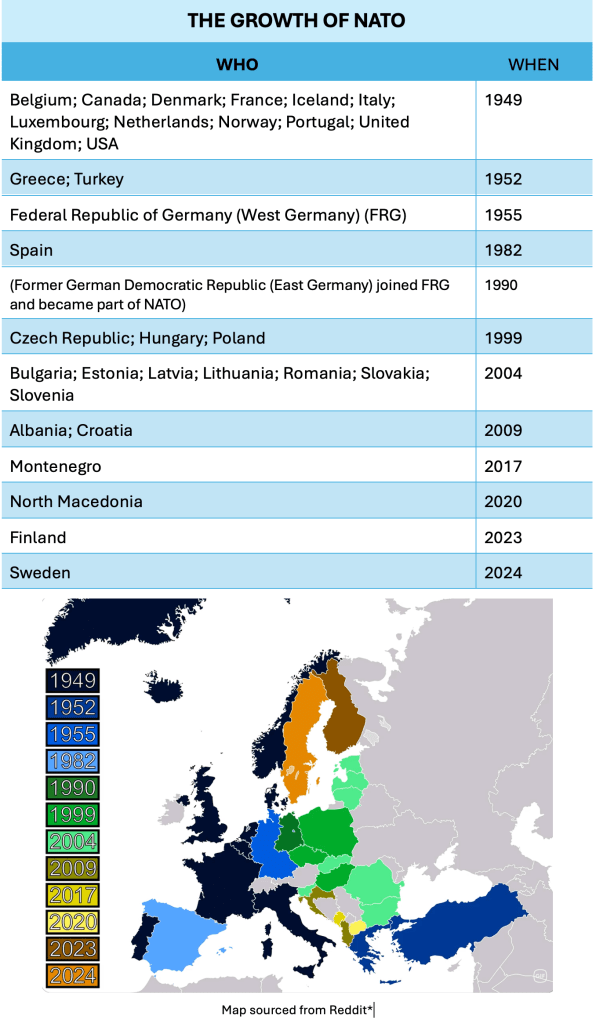

Twelve states founded the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation in 1949. 75 years later, there are 32. As the table and map at the end of this post show, the increase in membership did not happen all at once. Three states joined in the 1950s and one more in 1982 to take the number in the closing years of the Cold War to 16. Since then, the number has doubled but, again, not all at once. Three joined in 1999, a bunch of seven in 2004, and six more in the 20 years thereafter, with Finland and Sweden as the most recent adherents, last year and this year respectively.

NATO has always described these additions to its membership as a process of enlargement, resulting from democratic decisions by the new member states, while Russia and critics of NATO tend to use the term expansion, depicting a power play. It is treated by Russian officials, politicians and commentators and other critics of NATO as an important part of how the USA has tried to distort the shape of the world order to suit its own interests.

When the issue of this growth in number of NATO members is taken up by Russian officials and other critics, it is not all of equal concern. It is almost exclusively the NATO membership of six former members of the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact (Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia) and three former Soviet republics (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) that is the focus of anger and complaint.

But there is plenty of justification for NATO’s use of the non-pejorative term, enlargement: no state was forced to join, politicians who opposed joining lost power in elections, and referendums when held supported joining. The process wasn’t perfect – in the Hungarian referendum, to illustrate, 85 per cent of those who voted supported NATO membership, but a fraction under 50 per cent actually voted at all. Yet, though there were flaws, it is clear that joining NATO was, at that time around the turn of the century, the popular choice in the new member states. To claim otherwise would be ahistorical and ridiculous.

Twelve states founded the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation in 1949. 75 years later, there are 32.

There are, even so, two issues worth addressing even if it was, broadly speaking, a democratic choice. One is whether NATO misled Russian leaders and promised not to take on new members in Eastern Europe. The second is whether enlarging NATO was the right thing to do.

Has NATO lied?

The Russian argument includes the assertion that, as the Cold War came to an end, NATO undertook not to take in new members from eastern Europe. This is a quite widely held view but it is based on a misunderstanding that simplifies a nuanced situation.

There was no formal undertaking made by NATO that it would not incorporate new members to its east. In that sense there was no promise, which means NATO did not break faith when enlargement/expansion happened. To say otherwise, to assert that NATO made promises or undertakings, is simply not historically accurate. But there is an important however to come – in fact, two of them.

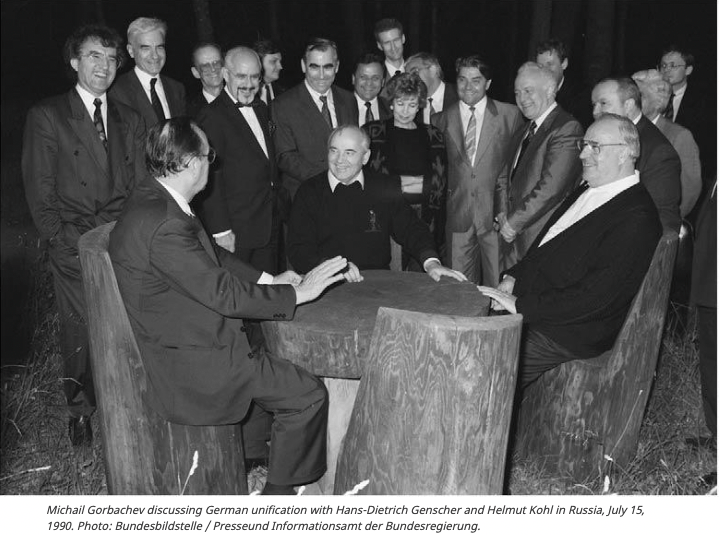

In the final years and months of the Soviet Union’s existence, however, statements were made to Soviet leaders that there would be no eastward enlargement. Key examples include the German foreign minister at the time, Hans Dietrich Genscher, saying in January 1990 that NATO would not grow to the east, and his US counterpart, James Baker, a few days later during a visit to Moscow, offering ‘ironclad guarantees that NATO’s jurisdiction or forces would not move eastward’, a position he modified in subsequent remarks. So some things were said but, of course, there’s another however.

However, these were statements of opinion, which in James Baker’s case was immediately and publicly amended. They were not binding on other NATO members and not even on Germany and the USA.

In addition, it seems sometimes to be forgotten amid the heat of the debate that there was actually a treaty that is relevant to this discussion – the treaty to reunify Germany. It was agreed in September 1990 by the German Democratic Republic (GDR) (East Germany), the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) (West Germany), France, the UK, the USA and the USSR: the two German states because they were the ones who were unifying, and the other four because they were the Four Powers who divided and occupied Germany at the end of World War II. Article 5(3) says that, after Soviet forces have withdrawn, foreign forces will not be stationed in the territory of the soon-to-be former GDR.

That is what the statements about not expanding eastwards came down to – not moving foreign forces eastwards within Germany. This is confirmed in an interview with Mikhail Gorbachev in 2014. His comment is worth quoting at length:

“The topic of “NATO expansion” was not discussed at all, and it wasn’t brought up in those years. I say this with full responsibility. Not a singe Eastern European country raised the issue, not even after the Warsaw Pact ceased to exist in 1991. Western leaders didn’t bring it up, either. Another issue we brought up was discussed: making sure that NATO’s military structures would not advance and that additional armed forces from the alliance would not be deployed on the territory of the then-GDR after German reunification.”

He adds that non-deployment of non-German forces in the ex-GDR was the context in which US Secretary of State Baker talked about ironclad guarantees.

On top of this, in 1990, Gorbachev also acknowledged the principle that states are free to choose their allies, implying that NATO might well accept new applicants into its membership. And in 1993, Russian president Boris Yeltsin agreed with Polish president Lech Walesa that Poland had the right to join NATO. Indeed, the NATO–Russia Founding Act signed in 1997 includes explicit reference (in Article IV) to ‘new members’ of NATO, indicating all parties’ (obviously, including Russia’s) acceptance of that prospect.

Of course, there is much about Gorbachev’s leadership of the USSR in its dying days, and about Yeltsin’s leadership of Russia through the low years of the 1990s, that the current Russian leadership and its supporters revile. It is not surprising if they want to undermine the validity of actions and statements of the Russian government of the time. Nonetheless, what was agreed was agreed, what was said was said, and what was not agreed was not agreed.

The Russian view focuses on the assurances that were offered, but misinterprets them, while the NATO view focuses on what was and was not included in binding and formal agreements.

The NATO view, then, is technically correct. But, as a top German foreign ministry official reportedly said in 1993, it is easy to understand why Yeltsin – and, by extension, other Russians – thought NATO had agreed not to take on new members. There is a kind of psychological reality here regardless of factual truth. Russian leaders and others can be forgiven for putting what was, for them, for assuaging their fears, the best possible gloss on what western leaders said, for perhaps paying too much attention to unguarded utterances that sounded reassuring. Whatever else, it is easy to understand Russian unease as NATO’s border came closer.

Was it right?

In keeping with its view of NATO’s culpability, in December 2021 Russia proposed two treaties, one with NATO and one with the USA that would have meant agreeing not to allow new members into NATO and, in particular, not Ukraine. There was no likelihood of NATO accepting this restriction. But it does reflect a genuine Russian view denying the legitimacy of NATO’s increase in size.

For a taste of the deep bitterness with which this view is held in Russia, here is President Putin in June, speaking to senior Russian foreign ministry officials:

“The Western powers, led by the United States, believed that they had won the Cold War and had the right to determine how the world should be organised. The practical manifestation of this outlook was the project of unlimited expansion of the North Atlantic bloc … They effectively forgot about the promises made to the Soviet Union and later Russia in the late 1980s and early 1990s that the bloc would not accept new members. Even if they acknowledged those promises, they would grin and dismiss them as mere verbal assurances that were not legally binding.”

It is notable how the Russian President elides two arguments – whether NATO lied and whether expansion was the right policy to follow – into one. I am not grinning when I say “those promises” were not even verbal assurances. The misunderstanding goes as deep as the bitterness and they probably strengthen each other on the way down.

But that leaves us with a legitimate question: even if NATO did not lie, was it right or wrong to get bigger? One critic of NATO’s growth was none other than George Kennan – often regarded as the architect of US ‘containment‘ of the USSR in the Cold War, though perhaps better seen as the one who best articulated the approach. In a 1997 article in the New York Times, he decried it as ‘a fateful error’. “Such a decision,” he argued, “may be expected to inflame the nationalistic, anti-Western and militaristic tendencies in Russian opinion; to have an adverse effect on the development of Russian democracy; to restore the atmosphere of the cold war to East-West relations, and to impel Russian foreign policy in directions decidedly not to our liking.” In May this year, Pope Francis said that while NATO’s presence in countries neighbouring Russia did not provoke the war, it “perhaps facilitated” the 2022 invasion. For this and similar comments, he has been accused of defending Putin but the core of his argument is close to Kennan’s.

Is that argument justified? One can certainly go item by item through Kennan’s warning and see each of these elements now in Russian policy and international relations. Does that nail the case?

If I were to get into either philosophy or social science theory at this point, I would ask about cause and effect and attribution. What Kennan foresaw has happened but the question is whether it happened because NATO got bigger.

I’m not sure there is a way to answer this. One school of thought may look at Russia’s war on Ukraine and say, ‘That’s what you get if NATO expands.’ Another group, however, is looking at Russia’s war on Ukraine and saying, ‘That’s what you get if you are not a member of NATO.’

Perhaps NATO could and should have handled these issues differently. I thought so at the time and it is certainly a discussion worth having. But it is hard to see moral equivalence between, on the one hand, what may have been diplomatic errors by the USA and its allies in the 1990s and, on the other hand, open aggression, systematic attacks on civilian targets, large-scale urban destruction and, if UN-collected evidence is borne out, abundant war crimes and violations of human rights.

In the end, when thinking about the war in Ukraine, the argument about NATO’s growth is just a digression.